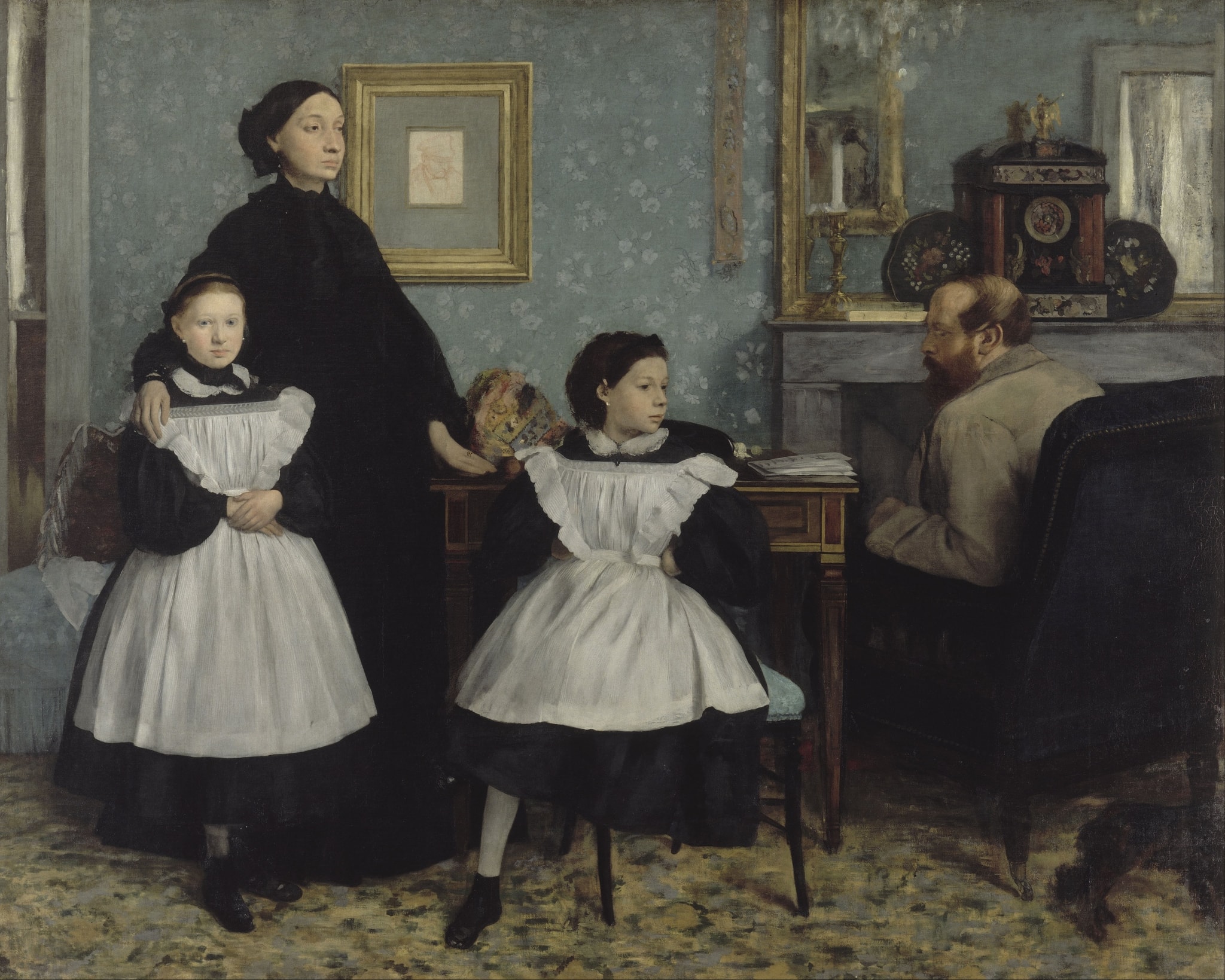

The Bellelli Family

by Edgar Degas

Fast Facts

- Year

- 1858–1869

- Medium

- Oil on canvas

- Dimensions

- 201 x 249.5 cm

- Location

- Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Click on any numbered symbol to learn more about its meaning

Meaning & Symbolism

Explore Deeper with AI

Ask questions about The Bellelli Family

Popular questions:

Powered by AI • Get instant insights about this artwork

Interpretations

Formal Analysis

Source: Musée d’Orsay; Theodore Reff

Social History / Material Culture

Source: Musée d’Orsay; Judith H. Dobrzynski

Gendered Spheres

Source: Musée d’Orsay; The Independent (Great Works)

Medium Reflexivity

Source: Theodore Reff; The Met (Boggs et al., 1988)

Political Subtext (Risorgimento Exile)

Source: Musée d’Orsay; The Met (Boggs et al., 1988)

Psychological Process / Making as Meaning

Source: Musée d’Orsay; The Met (Boggs et al., 1988); Wikipedia (summary of Danto)

Related Themes

About Edgar Degas

More by Edgar Degas

The Opera Orchestra by Edgar Degas | Analysis

Edgar Degas

In The Opera Orchestra, Degas flips the theater’s hierarchy: the black-clad pit fills the frame while the ballerinas appear only as cropped tutus and legs, glittering above. The diagonal <strong>bassoon</strong> and looming <strong>double bass</strong> marshal a dense field of faces lit by footlights, turning backstage labor into the subject and spectacle into a fragment <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Tub

Edgar Degas (1886)

In The Tub (1886), Edgar Degas turns a routine bath into a study of <strong>modern solitude</strong> and <strong>embodied labor</strong>. From a steep, overhead angle, a woman kneels within a circular basin, one hand braced on the rim while the other gathers her hair; to the right, a tabletop packs a ewer, copper pot, comb/brush, and cloth. Degas’s layered pastel binds skin, water, and objects into a single, breathing field of <strong>warm flesh tones</strong> and blue‑greys, collapsing distance between body and still life <sup>[1]</sup>.

The Ballet Class

Edgar Degas (1873–1876)

<strong>The Ballet Class</strong> shows the work behind grace: a green-walled studio where young dancers in white tutus rest, fidget, and stretch while the gray-suited master stands with his cane. Degas’s diagonal floorboards, cropped viewpoints, and scattered props—a watering can, a music stand, even a tiny dog—stage a candid vision of routine rather than spectacle. The result is a modern image of discipline, hierarchy, and fleeting poise.

Woman Ironing

Edgar Degas (c. 1876–1887)

In Woman Ironing, Degas builds a modern icon of labor through <strong>contre‑jour</strong> light and a forceful diagonal from shoulder to iron. The worker’s silhouette, red-brown dress, and the cool, steamy whites around her turn repetition into <strong>ritualized transformation</strong>—wrinkled cloth to crisp order <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.

The Rehearsal of the Ballet Onstage

Edgar Degas (ca. 1874)

Degas’s The Rehearsal of the Ballet Onstage turns a moment of practice into a modern drama of work and power. Under <strong>harsh footlights</strong>, clustered ballerinas stretch, yawn, and repeat steps as a <strong>ballet master/conductor</strong> drives the tempo, while <strong>abonnés</strong> lounge in the wings and a looming <strong>double bass</strong> anchors the labor of music <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[3]</sup><sup>[4]</sup>.

Place de la Concorde

Edgar Degas (1875)

Degas’s Place de la Concorde turns a famous Paris square into a study of <strong>modern isolation</strong> and <strong>instantaneous vision</strong>. Figures stride past one another without contact, their bodies abruptly <strong>cropped</strong> and adrift in a wide, airless plaza—an urban stage where elegance masks estrangement <sup>[1]</sup><sup>[2]</sup>.